Forecasting today was quite interesting. The deep-layer shear was oriented such that storms were expected to move mostly south to north, and terrain was a larger consideration than it normally is. There is a highly detailed topography map that we can have up while issuing forecasts, and terrain features guided the placement of some of our probabilities. Terrain can help initiate storms by providing a source of heating at a high elevation, where the surrounding air is typically cooler than it would be at a lower elevation. Low dew points are a common concern in the west and today was no exception - large areas of high instability were be difficult to come by. However, convection was ongoing this morning, suggesting that some instability was present and taking advantage of the strong dynamic forcing over our area of interest to generate storms.

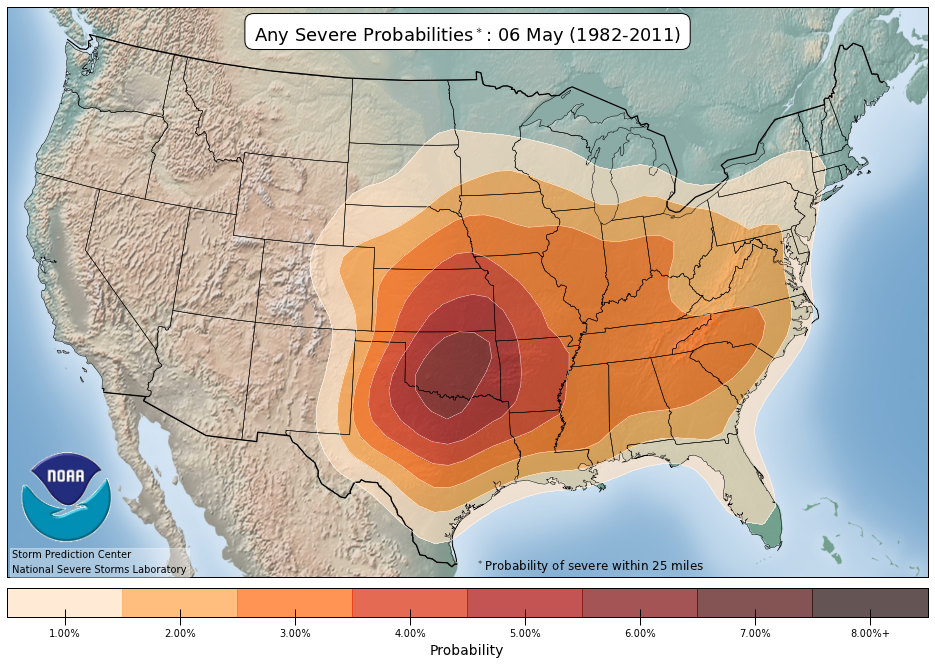

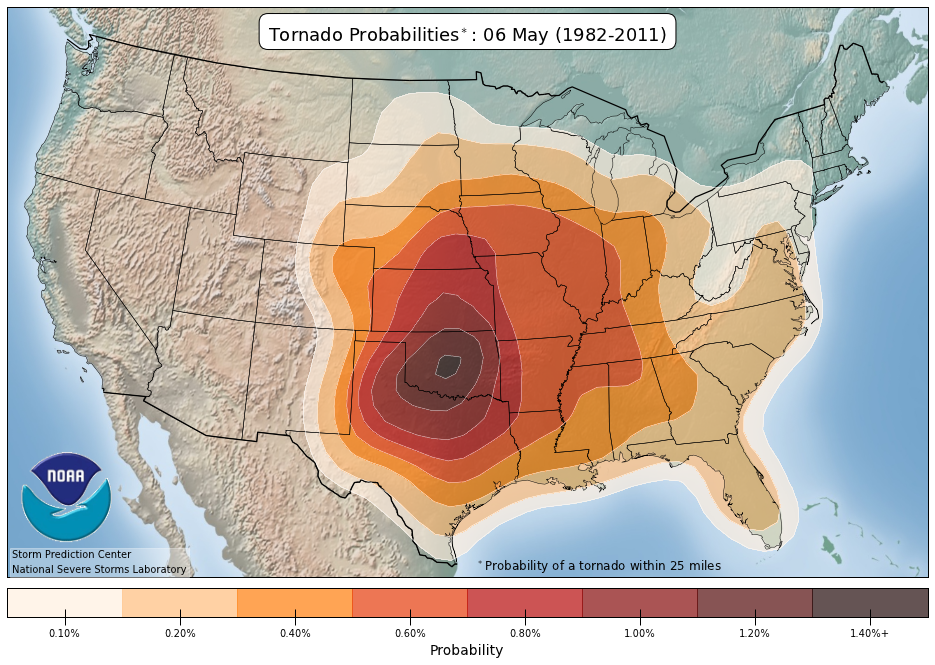

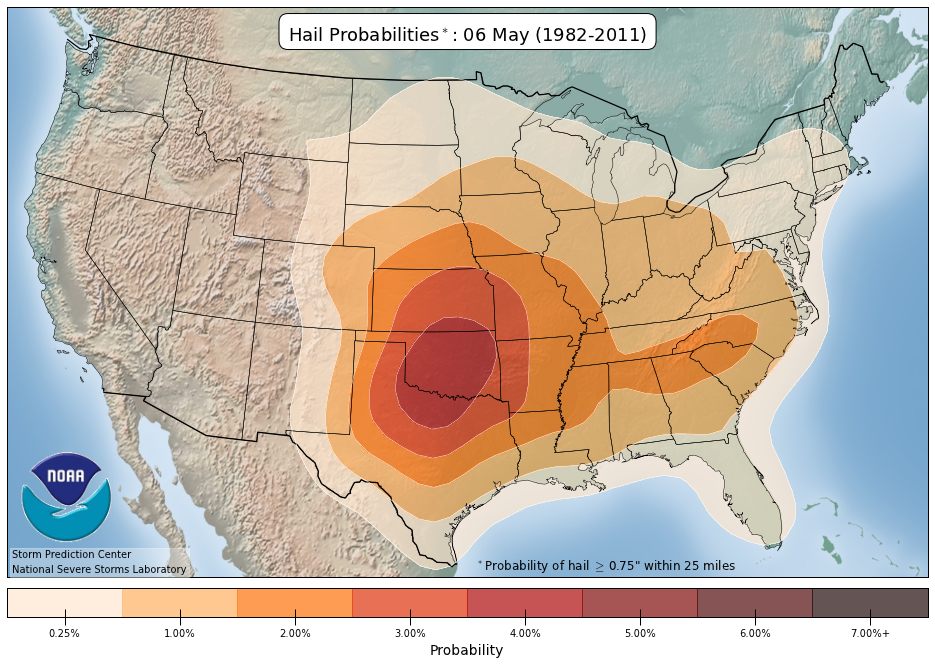

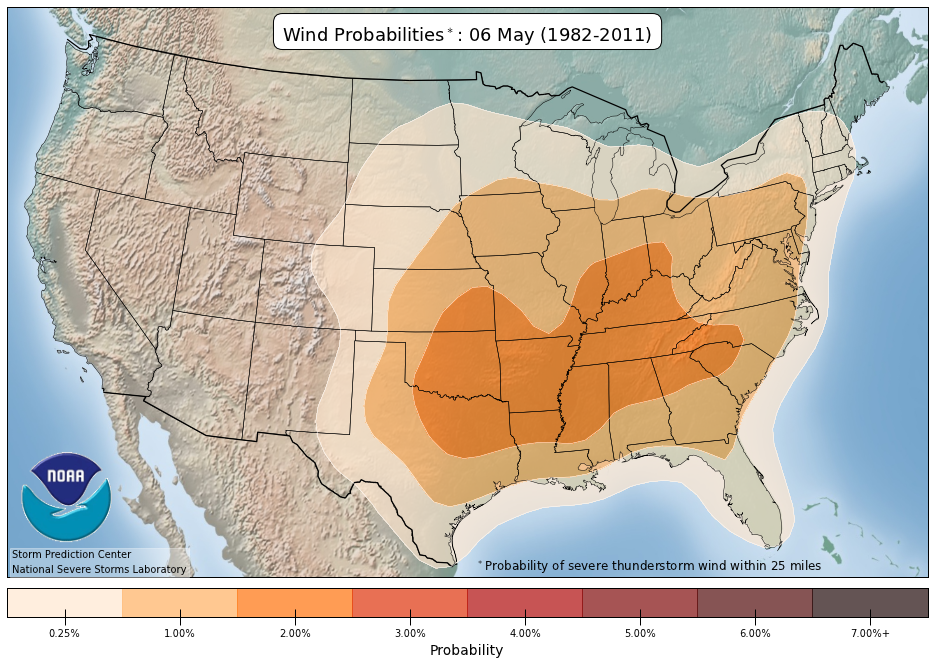

But how climatologically unusual is a severe event west of the Rockies in early May, particularly as far north as Oregon? To begin to answer this question, we can consider the severe climatology maps produced by the SPC on 6 May.

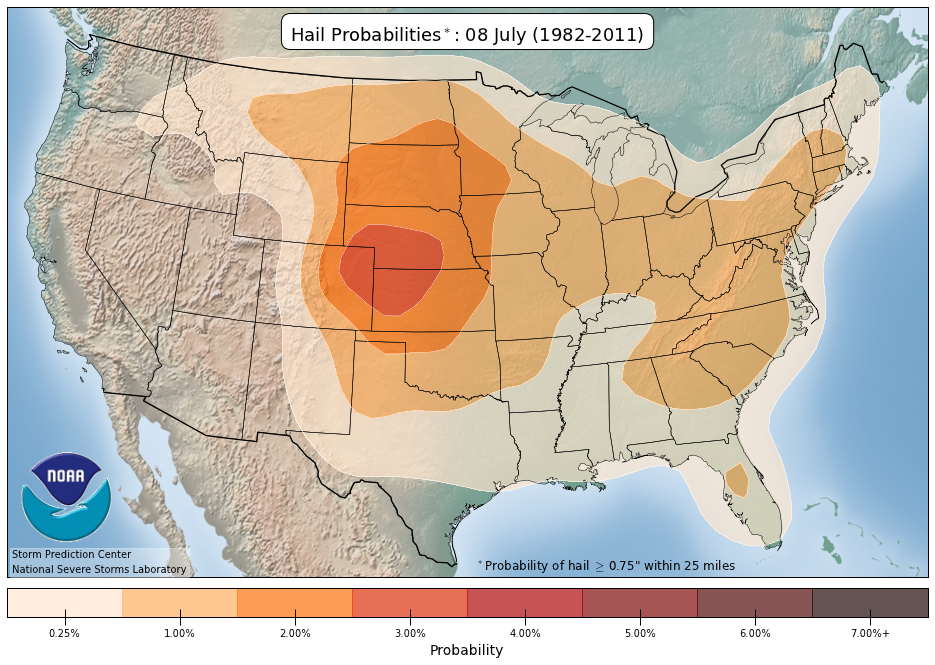

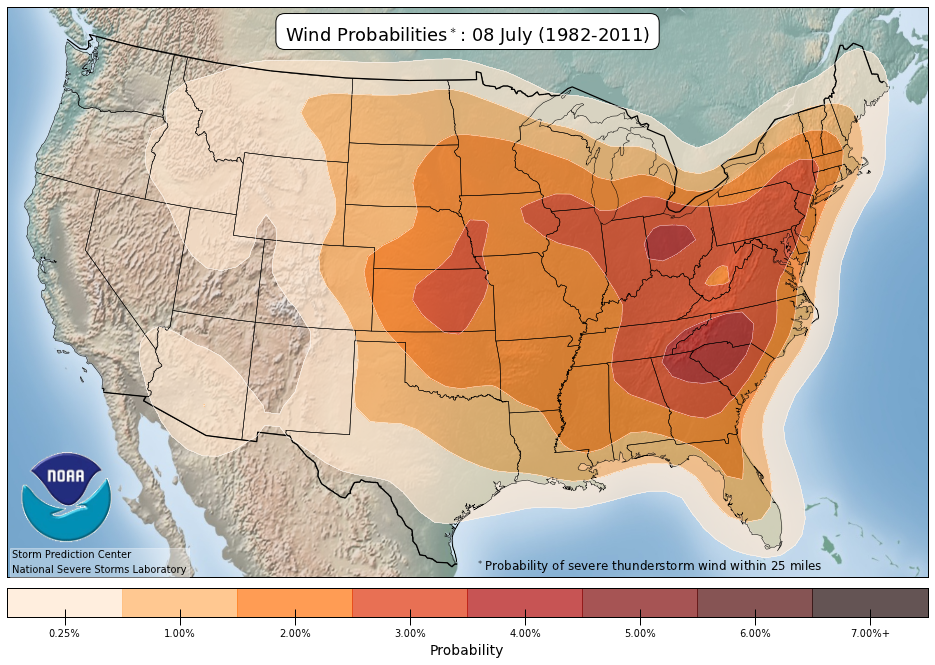

From these maps, we can see that the climatological probability of any severe hazard is extremely low to the west of the Great Plains, not even exceeding 1%. The individual hazard probabilities tell a similar tale:

Each of these hazards has less than a .25% occurrence climatologically, according to the reports from this day across a 30-year period.

So, when is the most favorable time for severe weather across this region? According to this data set, there really isn't a discernible peak in tornado reports. With a 30-year average of 5 annual tornadoes in Idaho and 2 annual tornadoes in Oregon, a lack of climatological probabilities isn't too surprising. However, both hail and wind probabilities remain below.25% until July.

According to these probabilities, it's unsurprising that the Spring Forecasting Experiment has never gone this far west before or that domain-limited convection-allowing guidance was focused on the eastern two-thirds of the United States.

As of ~0400 UTC a couple of hail reports have come in from Oregon, and they have occurred since 0000 UTC. Storms appear to be ongoing, although radar coverage in mountainous terrain is spottier than elsewhere due to beam blockage. Tomorrow's verification should have some good discussion about the quality of our westernmost area of interest yet, including how well the convection-allowing guidance performed in a relatively new region.

No comments:

Post a Comment